Each growing season is a new beginning for wine producers. In marginal climates ripening can be challenging, and hazards like frost, hail, and fungal disease lurk at every turn. With this in mind, stellar years, like the 2019 vintage Burgundy recently experienced, are to be treasured.

After a mild winter, cool weather set in over spring, with April frost episodes – notably in the Mâconnais region- threatening the crop. The unseasonably chilly conditions lasted through June leading to uneven flowering and fruit set in certain sectors. The thermostat shot up in July and August, with spells of extreme heat leading to sunburnt grapes and hydric stress in many vineyards. Harvest came early, with a small crop of ripe, compact grapes. Despite the season’s challenges, 2019 vintage Burgundy is being hailed by many critics as highly promising.

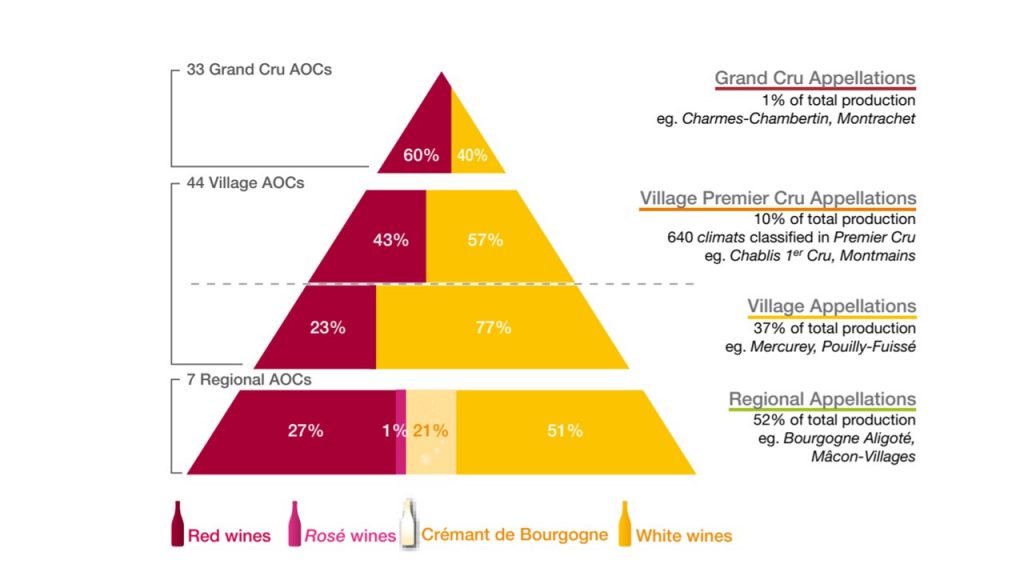

According to the Bureau interprofessionnel des vins de Bourgogne (BIVB), the overall yield of 2019 vintage Burgundy was some 15% below average, at 1.23 million hectoliters. The low volume and reports of universally high quality across all regions and wine styles will likely equate to rising Burgundy prices once again. While this is bad news for Burgundy lovers, these ripe vintages result in excellent quality wines from less prestigious appellations. Read more on this here.

Surprisingly, given the prolonged summer heat waves and drought episodes, the 2019 vintage Burgundy report from the BIVB speaks of vibrant acidity levels from Chablis down to the Mâconnais, ably balancing ripe fruit flavours and rich, textural palates.

Curious to taste such a vaunted vintage, for both white and red wines, across the vast expanse of the Burgundy region, I gladly accepted an offer of en primeur samples from Bourgogne de Vigne en Verre. This group of 35 wine producers from Chablis to Mâcon, have joined forces to jointly promote their wines at home and abroad.

The 36 bottles of 2019 vintage Burgundy arrived cleverly packaged in 20mL single serving formats. After letting them rest for a few days, I sat down with my favourite oenologist (aka my husband) and we got down to tasting.

Overall, we found that the 2019 vintage Burgundy wines showed real appellation typicity despite/alongside a ripe, fragrant fruit-forward style. On the whole, the wines were fresh, densely structured, and quite concentrated on the palate. For the most part, the red wines had ripe, approachable tannins with the best showing a tempting, almost chocolatey appeal. Some evidence of warming alcohol, freshness fading on the finish, and chewy tannins was also found in less successful examples.

In true Burgundian fashion, here are my 2019 vintage Burgundy tasting notes – red wines followed by whites:

RED WINES

Côte Chalonnaise

Domaine Meix-Foulot Mercurey 1er Cru “Clos de Château de Montague” : Moderately intense aromas of ripe raspberry, morello cherries, and hints of spice. Brisk and taut on the palate, with rustic savoury flavours underlying bright red berries. Faintly chewy tannins on the short finish. 86pts.

Domaine Meix-Foulot Mercurey 1er Cru “Les Veleys” : Bright red fruit, floral and blackberry hints on the nose. Crisp and somewhat angular on the attack, giving way to a smooth mid-palate, and fine-grained tannins. 87pts.

Domaine Meix-Foulot Merc 1er “Les Saumonts” : More restrained on the nose, with subtle red fruit and barnyard hints emerging with aeration. Similarly styled on the palate – brisk and taut – but with very fine, elongated tannins and a marginally longer finish. 87pts.

Domaine Chofflet Givry 1er Cru “Clos Jus”: High toned red berry, cherry, and marzipan notes on the nose. Lively and light on the palate with a silky texture, moderate depth of ripe dark fruit and kirsch flavours. Finishes smooth and fresh. – 88pts.

Domaine Chofflet Givry 1er Cru “En Choué” : Fragrant floral notes on the nose, with pretty red berry undertones. The palate shows a lovely ripeness of fruit, balanced by bright acidity and firm tannins. 90pts.

Côte de Beaune

Domaine Labry Hautes Côtes De Beaune: Intense aromas of crushed strawberry on the nose. Fresh and rounded, with a soft, short finish. Drink now. 86pts.

Domaine Labry Auxey Duresses: Perfumed notes of prunes, baking spice, and dark berry jam. Initally bright, but with a faintly bitter, hard edge to the baked fruit flavours. Soft tannins. 85pts.

Domaine Edmond Cornu Chorey-Les-Beaune “Les Bons Ores” : Delicate strawberry, cherry, and earthy nuances on the nose. Fresh, precise and firm in structure, with moderate concentration of tangy red berries and nutty flavours. Attractive chalky tannins frame the finish. 89pts.

Domaine Edmond Cornu Aloxe-Corton: Pretty nose featuring ripe black berries, morello cherry, and violets. Brisk and polished on the palate, with juicy black and red fruit flavours well knit with toasty spiced nuances. Silky tannins linger on the finish. 91pts.

Domaine Edmond Cornu Ladoix: Similar to Cornu’s Aloxe on the nose, with a slightly riper, more fruit-forward charm. Medium in body, with a firm texture verging on austere yet balanced by good depth of fruit and ripe tannins with an almost chocolatey sweetness. 90pts.

Domaine Georges Lignier Volnay 1er Cru: Complex, highly perfumed nose of ultra-ripe red fruits, with underlying notes of peony, sweet spice, and dried herbs. Really tangy, vivid acidity on the palate giving way to a silky, medium bodied palate with bright fruit flavours, and a lifted finish. Needs a few years to soften. 92pts.

Domaine Edmond Cornu Ladoix 1er Cru “Le Bois Roussot”: Moderately intense aromas of pomegranate and macerated red cherry, underscored by dark fruit and spice hints. The palate is fresh, with a concentrated core of sweet red fruit, balanced by lifted, tangy flavours on the finish. Slightly warming, with firm, chewy tannins. 90pts.

Domaine Edmond Cornu Corton-Bressandes Grand Cru: Initally discreet, with complex aromas of morello cherry, orange peel, underbrush, floral nuances, and spice developing with aeration. The palate is fresh and lively, with a weighty core, velvety texture, and ultra-fine, powdery tannins. Elegant, with lingering stony minerality. 95pts.

Côte de Nuits

Domaine Jean Chauvenet Nuits-St-Georges: Intense notes of morello cherry and cassis on the nose, with earthy undertones. Lively on the attack, though somewhat rustic on the mid palate with a certain graininess of texture giving way to dense tannins. Soft fruit and earthy, underbrush nuances on the finish. 86pts.

Domaine Jerôme Chezeaux Vosne-Romanée: Intense, fairly complex aromas of crushed strawberries, morello cherry, marzipan, mixed spice, and violets on the nose. The palate is initially vibrant and suave, with medium body, and concentrated red and black fruit flavours, which become slightly overpowered by cedary oak nuances and somewhat drying tannins on the warming finish. 89pts.

Domaine Philippe Cheron Vosne-Romanée “Les Barreaux”: this high quality climat sits just above Richebourg. Initially restrained, with a multitude of ripe to macerated red fruits unfurling with aeration, underscored by layers of dried fruit, spice, floral, and nutty aromas. Dense and voluptuous on the palate, with suave rounded tannins, and a fresh, persistent flavourful finish. 93pts.

Domaine Philippe Cheron Chambolle Musigny “Clos de L’Orme”: Another well situated plot, lying just beneath Les Charmes and Les Plantes. Perfumed notes of morello cherry, dark plum, citrus oil, dried red fruits, and baking spice on the nose. The palate is wonderfully bright, with medium body, and concentrated fruit flavours that mirror the nose. Velvety tannins finish the medium length, marginally warming finish. 92pts.

Domaine Philippe Cheron Chambolle Musigny “Les Quarante Ouvrées”: Similarly ripe, expressive nose as the “Clos de L’Orme”; slightly more marked by its élévage with toasted, mocha nuances that will likely soften over time. Very silky and textural on the palate, with fine, smooth tannins. Light and elegant. 92pts.

Domaine Philippe Gevrey-Chambertin “Le Meix des Ouches”: out of condition

Domaine Georges Lignier Gevrey-Chambertin: Intense, nuanced nose with layers of marzipan, dark cherry, cassis, violets, and attractive herbal undertones. Incredibly lively on the palate, with layers of juicy black fruit flavours, quite a firm structure, and ripe, fine-grained tannins. Balanced and long. 92pts.

Domaine Jean Chauvennet Nuits-St-Georges 1er Cru “Les Perrières”: Stewed dark cherry and plum notes mingle with undertones of leather, dates, and allspice on the nose. Very firm and brisk on the palate, giving way to a highly concentrated core of dark fruits, savoury notes, and cedar spice. Bold, yet ripe, elongated tannins frame the long, layered finish. Needs a few years’ cellaring to unwind. 91pts.

Domaine Jean Chauvennet Nuits-St-Georges 1er Cru “Les Vaucrains”: out of condition

Domaine Jean Chauvennet Nuits-St-Georges 1er Cru “Rue de Chaux”: Attractive, highly expressive nose of blackberries, plum, and cassis, with underlying stony minerality and well integrated cedar, spiced nuances. Firmly structured but generously fruity and polished on the palate, with muscular tannins. Excellent length. 94pts.

Domaine Jean Chauvennet Nuits-St-Georges 1er Cru “Les Bousselots”: Quite a different offering than the Rue de Chaux, though equally complex. Macerated red berry and cherry aromas are underscored by kirsch, underbrush, and savoury nuances on the nose. The palate is tightly wound, with mouth watering acidity, and very firm, yet fine-grained tannins. Needs a good five years + in cellar to soften. 90pts.

Domaine Jerôme Chezeaux Nuits-St-Georges » 1er Cru “Aux Boulots”: Quite restrained on the nose, with ripe black berry and cherry notes, violets, and marzipan notes emerging after a period of aeration. This Nuits really comes in to its own on the vibrant, juicy fruited palate, with its elegant structure, fine-grained tannins, and long, vivid finish. Very harmonious. 94pts.

Domaine Jerôme Chezeaux Vosne Romanée 1er Cru “Les Chaumes”: Highly perfumed, with sweet aromas and flavours of ultra-ripe blackberry, plum, and raspberry, mingled with floral and citrus peel notes. Brisk and firm on attack, deepening on the mid-palate, and finishing taut with densely wound tannins. Needs time to resolve but shows excellent potential. 93pts.

Domaine Georges Lignier Morey St Denis 1er Cru “Clos des Ormes”: Already quite tertiary on the nose, with crushed strawberry notes overshadowed by aromas of prunes, leather, and dried herbs. Fresh on the palate, with both tart and ultra-ripe fruit flavours vying for primacy. Attractive chalky texture and tannins. 89pts.

Domaine Philippe Cheron Gevrey-Chambertin 1er Cru “Champonnet”: Intense mocha, toasted, nutty aromas, slightly overpowering dark fruit notes. The palate is somewhat angular, with mouth watering acidity, a firm structure, and somewhat lean mid-palate. 88pts.

Domaine Philippe Cheron Gevrey-Chambertin 1er Cru “La Romanée”: Ripe red and black berry fruit on the nose, with attractive hints of baking spice, nutty nuances, and subtle florality. Vivid and dense on the palate, with tangy acidity, and a concentrated core of dark fruit. Somewhat rustic, chewy tannins on the medium length finish. 89pts.

Domaine Georges Lignier Gevrey-Chambertin 1er Cru “Les Combottes”: Les Combottes is surrounded by illustrious neighbours including grand crus: Mazis-Chambertin and Latricières-Chambertin. This 1er Cru offers restrained cassis and plum notes on the nose. The palate is firm, with animal nuances, and grippy tannins. 87pts.

Domaine Philippe Cheron Clos Vougeot Grand Cru: Moderately intense notes of marzipan, plum, and dark cherry with animal undertones. Brisk and tightly wound on the palate, with a dense, concentrated structure, and firm, moderately astringent tannins. 87pts.

Domaine Philippe Cheron Charmes-Charmbertin Grand Cru: Discreet on the nose, with mocha, cedar, and spice aromas after aeration. The palate is dense, velvety, and broad, with concentrated, ultra-ripe fruit flavours underlying bold, toasted oak flavours. Firm, somewhat grippy tannins. 88pts.

Domaine Georges Lignier Clos St Denis Grand Cru: Vibrant herbal, blackcurrant bud aromas mingle with red currants and earthy, underbrush nuances on the nose. The palate is quite taut and weighty, with firm, lifted acidity and dense, chewy tannins. 87pts.

Domaine Georges Lignier Clos de la Roche Grand Cru: Fragrant, floral nose with vivid crushed raspberry, morello cherry, and black berry fruit aromas. Over time, mixed spice and citrus oil notes emerge. The palate is lively and firm, with quite a powerful structure, and concentrated flavours. The tannins are grippy and taut on the long finish. Needs time to soften. 90pts.

WHITE WINES

Domaine Labry Bourgogne Hautes Côtes de Beaune: Delicate notes of red apple and white blossoms on the nose. The palate is crisp on the attack, giving way to a broad, rounded, supple mid-palate with lingering lactic nuances. Finishes smooth and soft. 86pts.

Domaine Beaufumé Chablis: Discreet lemony, green apple nose. Light and racy on the palate, with subtle mineral hints. 87pts.

Domaine Chofflet Givry 1er Cru “Les Galaffres”: Attractive poached pear, red apple, and spiced aromas on the nose. The palate is crisp and very juicy, with a rounded, ultra-smooth appeal. Tangy orchard fruit notes linger on the finish. Harmonious. 90pts.

Domaine de Montarge Montagny 1er Cru “Montorge”: Pretty floral nose, with underlying yellow orchard fruit, and lactic hints. Initially fresh with a supple, creamy mid-palate, and fairly short, somewhat flabby finish. 87pts.

Domaine Labry Auxey Duresses: Vibrant nose featuring ripe lemon, white fleshed orchard fruits, and hints of anis. Searing acidity on the palate leads into a taut, moderately concentrated core, with tangy citrus notes. Finishes fresh with hints of attractive bitterness. 88pts.

Lavantureux Frères Chablis 1er Cru Fourchaume: Classic, highly complex aromas of red apple, flint, ripe lemon, white blossoms, and fresh almonds unfurl on the nose. The palate is racy and firm, yet broadens on the mid palate revealing a creamy, textural core with concentrated fruity, mineral flavours. Very precise, elegant, and long. 94pts.

Lavantureux Frères Chablis Bourgros Grand Cru: Ripe, sweet orchard fruit aromas mingle with white peach, anis, and toasted nutty aromas on the powerfully nuanced nose. Crisp acidity lifts the concentrated, layered mid-palate, and underscores vivid yellow fruit and brioche flavours. Smooth and harmonious on the long finish. 95pts.