Last month in Montréal, an important event took place. Hundreds from the global wine trade gathered, in-person and online, to discuss the most pressing issues facing our industry. The two-day Tasting Climate Change conference saw renowned experts from around the world come together to raise awareness of the urgent changes we need to be making.

As we are now all too painfully aware, human-induced global warming has resulted in unprecedented changes to the Earth’s climate. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the last decade has been warmer than any period in roughly 125 000 years. Concentrations of carbon dioxide in our atmosphere have been unmatched for over 2 million years. Glacial retreat is occurring at unprecedented levels. Water levels are rising, our oceans are warming, and they are acidifying.

No one, no industry, and no corner of the earth is impervious to these dramatic changes. In the wine world, the signs are all around us. Warming temperatures are pushing the vine’s growth cycle forward, exposing tender buds to increased risk of spring frost damage in many cooler areas. Extreme and/or erratic weather patterns have heightened the frequency and severity of hail, floods, wildfire outbreaks, drought, changing pest and disease pressures, or brutal vine killing winters. Every wine region has its own set of challenges.

And despite this dire situation, the Tasting Climate Change Symposium was far from a two-day gloom fest. “There is still a lot of hope out there” insisted conference founder and wine climate change expert, Michelle Bouffard, in her opening speech. “There are so many brilliant and passionate people working to find solutions”. This is what we experienced over two days of presentations and urgent dialogue.

Of course, it is impossible to dig deeply into a topic in a mere hour-long panel discussion. The point of the event wasn’t to gain consummate knowledge or come to any sort of resolution. The goal was to plant a seed; to inspire attendees to explore the issues further themselves, to share their learnings with the wider community, and to find new ways to collaborate.

Soil health and management were major topics. Marc-André Selosse PhD, Professor at Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle of Paris, explained that healthy soils, those teeming with life and rich in organic matter, are the most critical defense against water shortages, and anchor for strong, resilient vines.

Soil, as we know, is a massively important resource for carbon sequestration. Maintaining cover crops, increasing soil organic matter, reducing external inputs, diversifying crops were all explored in a fascinating session on regenerative agriculture with the technical directors or owners of Bonterra Organic Estates, Château Patache d’Aux, and Michel Gassier.

Etienne Neethling PhD, head of the international master programme in vine, wine, and terroir management at the Higher School of Agriculture in Angers, France presented his research on building climate resiliency into vineyards. One of Neethling’s current research focuses is the existing clonal diversity in many major wine grapes and their ability to boost climate resilience in vineyards.

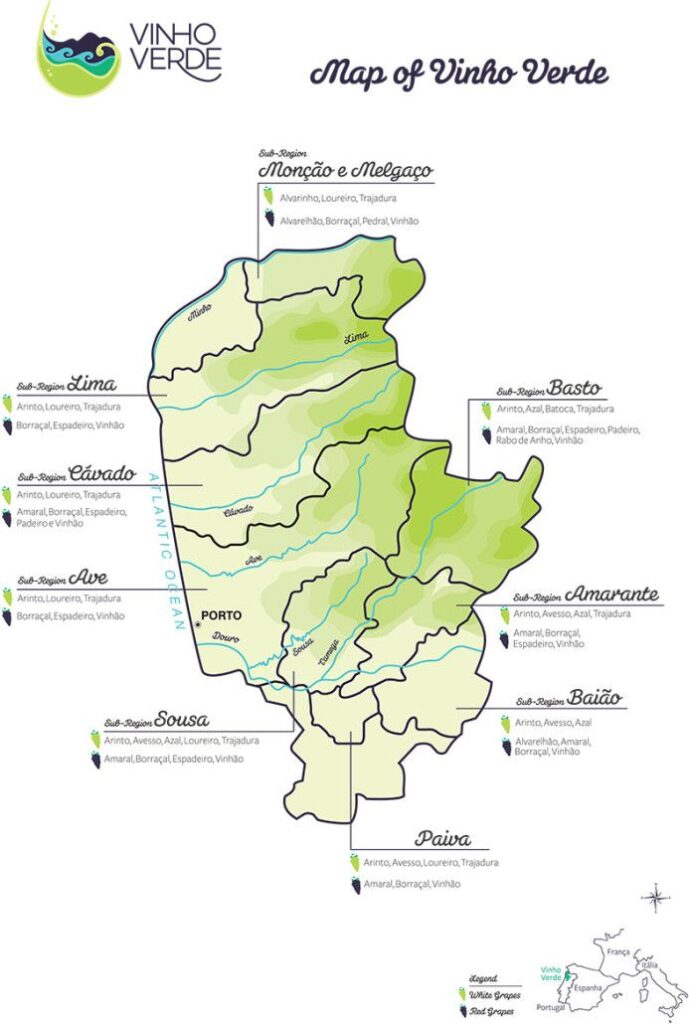

Many regions are exploring potential shifts in Vitis vinifera varieties planted or introducing hardier hybrids. Instead, Neethling proposes an alternate route for vineyard regions firmly linked to their signature grapes. Planting a wider diversity of grape clones, with a mix of earlier and later ripening properties, and differing resistances to stresses like drought, cold, vineyard pests and diseases.

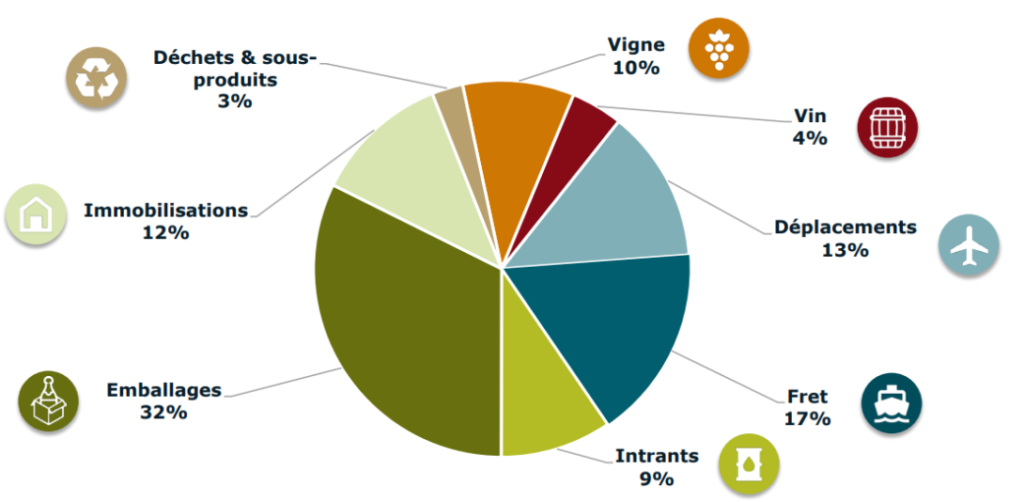

Representatives from the impressive Sustainable Winegrowing New Zealand organization (SWNZ) and the Comité Champagne shared their work on measuring carbon footprint in wine production. Both regions are gunning for carbon neutrality by 2050.

In New Zealand, greater water efficiency, reduced diesel fuel usage, and zero waste to landfill are just three target areas. Among their many achievements, SWNZ has implemented personalized benchmarking reports for all certified wineries, that outline their total greenhouse gas emissions, with comparative industry totals.

In Champagne, an outright ban on pesticide use is in the works. Packaging, which accounts for up to 40% of a wine’s carbon footprint, is another major preoccupation here. While sparkling wine bottles need to be heavier to withstand the immense pressure within, improvements are possible. The Comité Champagne was able to lightweight their bottles from 900g to 835g and increased recycled glass usage to 96%, reducing CO2 emissions by 8000 tons annually.

So many other great topics were explored, from ways to adapt to shifting pest and disease pressures, to the role of agroforestry in regulating climate and augmenting biodiversity, to the importance and potential confusions around the plethora of eco certifications that exist today.

The conference did indeed achieve its purpose. I saw countless exchanges between wineries, regional bodies, retailers, and journalists from across the globe – comparing notes and sharing best practices. For me, the biggest takeaway is that we must stop trying to dominate nature, but rather work within its bounds, harnessing nature’s innate power to provide its own solutions.

Rather than spraying fungicides, Matthieu Beauchemin, of Domaine du Nival, decided to create wind corridors and focus on aerating his vines, among other natural measures, to diminish mildew outbreaks. He also learned to live with low levels of fungal infections as part of the seasonal cycle.

The solutions proposed to a myriad of climate related issues throughout the two days, were creative, tailored to individual situations, and, moreover, focused on going beyond sustainability. They sought to improve and restore what has been lost.

For many of us, though, our part to play in fighting climate change remains nebulous. What can we do when we are not the producer, the transporter, or any other of the major greenhouse gas emitters in a wine’s lifecycle? So much…

We can choose what we promote to our audiences, be it followers or friends, and we can choose what we buy. We can boycott the big, heavy bottles, and instead champion the efforts of wineries, like Stratus Vineyards, who have chosen to put even their premium wines in featherweight (370 gram) bottles. We can also orient our drinking habits towards wines from sustainable or organic or, regeneratively farmed vineyards.

It may not always be clear what the most sustainable or ecologically conscious choice is, but if we start small, seeking out information on bottle stickers and back labels, asking questions at cellar doors, we can all make the tiny, incremental changes that collectively make a big impact.