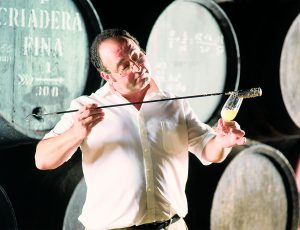

Photo credit: us.riojawine.com

The past twenty odd years has been an exciting time in the winemaking world. So-called ‘New World’ producers have resoundingly proven that they can compete on the global stage, and a new generation of ‘Old World’ growers have emerged. This latter group is travelling more and embracing modern technologies; refining the styles of their wines as they go.

The result is a blurring of the lines, whereby the clichéd characteristics of certain wines and regions no longer apply. Wines made oceans apart, in dramatically different climates and soil types, are surprisingly similar. While others, made two cellars down in the same village, bear little ressemblance.

This situation has many traditionalists shaking their heads, and looking back longingly to a time when Chablis was Chablis, and nothing else came close. I’ll admit that, when blind tasting, the lazy part of me secretly wishes that all regional wines fit their textbook descriptions. And yet, how boring life would be for winemakers were they all to make the same wines as their neighbours.

Rioja is a prime example of a region that has undergone significant stylistic changes in recent years. The stereotypical definition of ‘classic Rioja’ is a pale garnet coloured red, with soft red fruit, heavy American oak influence (vanilla, dill flavours) and a mellow, tertiary character from prolonged barrel maturation (soft tannins, leather and dried fruit nuances). The traditional whites are heavily oxidized; deep gold in colour with nutty, honeyed flavours.

At the opposite end of the spectrum, ‘modern Rioja’ is often inky dark in colour, with fresh acidity, ripe black fruit aromatics, firm tannins and French oak flavours (spice, cedar). Tempranillo is still king, but Garnacha (Grenache), Mazuelo (Carignan) and Graciano are bigger supporting players here. The whites now run the gamut from crisp, lean and unoaked through to full bodied, rich and lavishly oaked (the barrel maturation periods are shorter however, resulting in fresher, fruitier wines).

The shift in styles may seem fairly radical, and does tend to cause a certain amount of nostalgic muttering amongst traditionalists. Yet when we look at the evolution of Rioja wines over the regions’ long history, it becomes apparent that change is the constant and not a recent trend.

Prior to the 18th century, Rioja wines were not aged in oak. Barrels were used strictly as a means of transport for exported wines, and lined with resins that negatively impacted the flavour profile. It wasn’t until local vineyard owners began visiting cellars in Bordeaux and consulting with French oenologists in the mid 1800s, that barrel ageing came to Rioja. The practice quickly caught on, and increasing numbers of wineries began maturing their wines in French oak.

The move to American oak came about as a cost saving measure in the early 19th century, as it could be imported cheaply from Spain’s overseas colonies and coopered locally. The duration of oak ageing became a gauge of quality, with soft, sweet vanilla scented reds ruling the pack.

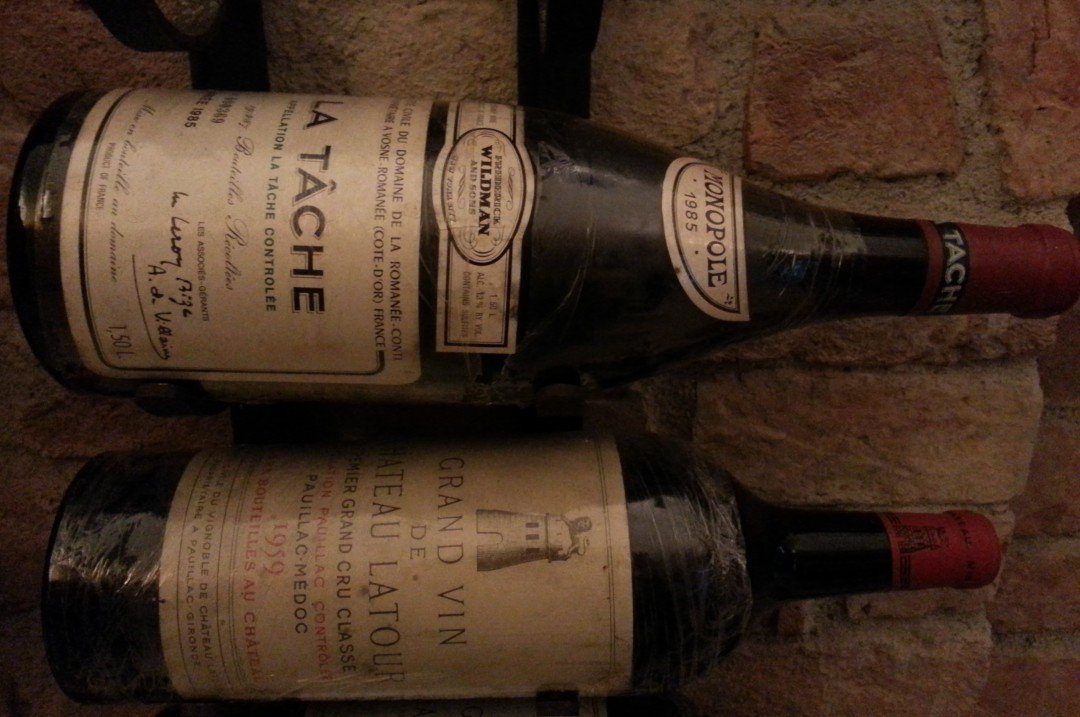

The ageing classifications of Crianza, Reserva and Gran Reserva only came about some forty years ago. Prior to that, consumers had little way of knowing how long a Rioja had slumbered in barrel. Vibrantly fruit, Beaujolais-esque reds co-existed with pale, mellow wines of 20 or more years’ oak maturation.

If anything, this labeling legislation has been a boon in bringing greater transparency and consistency of style to Rioja wines, whereby (for reds):

Crianza: 2 years’ minimum ageing (at least 1 year in barrel)

Reserva: 3 years’ minimum ageing (at least 1 year in barrel)

Gran Reserva: 5 years’ minimum ageing (at least 2 years in barrel)

And while the fashion for denser, riper fruited, fuller-bodied Rioja continues to gain traction, there remain a large number of stalwarts who continue crafting their wines along fairly classical lines (López de Heredia, CVNE, Marqués de Murrieta, Muga, Marqués de Riscal, just to name a few).

These producers may not age wines in barrel for as long as they once did, and many now prefer a mix of American and French oak, but the mellow appeal and sweet fragrance are not lost. The wines have simply gained in freshness and vibrancy.

Here are a list of great classic and modern Riojas to try from a recently attended tasting (What do VW, PW and LW mean? Click on my wine scoring system to find out).

Conde Valdemar, Finca Alto de Cantabria 2015 (white) – 93pts. VW

At just shy of 20$, this suave, beautifully balanced white offers fantastic value. Toasty, vanilla oak aromas are ably matched by attractive candied pear, honey and spiced notes. The palate is tangy and fresh, with a creamy, layered centre and bright fruit lingering on the finish.

Blend: 100% Viura

Where to buy: SAQ (19,85$)

Rioja Vega Tempranillo Blanco 2015 (white) – 89pts. PW

A mutation of the red Tempranillo grape, Tempranillo Blanco has only been approved for use in white Rioja wines since 2007. This lively example is laden with ripe, red apples, yellow pear and floral nuances. Medium bodied, smooth and moderately creamy, this easy drinking white boasts a long, delicately oaked finish.

Blend: 100% Tempranillo Blanco

Where to buy: LCBO (21,95$) SAQ (22,95$)

Dinastia Vivanco “Seleccion de Familia” Crianza 2012 (red) – 88pts. VW

Attractive, spiced strawberry and candied cherry notes are underscored by earthy nuances on the nose. The palate is dense and firm in structure, with brisk acidity. A moderately concentrated core of tart red fruits lifts the mid-palate. The finish is framed by ripe, grainy tannins and subtle cedar, vanilla oak.

Blend: 100% Tempranillo

Where to Buy: SAQ (19,95$)

Bodega Palacios Remondo “La Montesa” 2013 (red) – 90pts. VW

Breaking away from the traditional Tempranillo led style, this tempting red is predominantly Grenache-based. Intense aromas of stewed strawberries, mixed spices and fresh, herbal notes feature on the nose. The palate offers wonderful vibracy, with nice depth of flavour and firm, yet ripe tannins. Hints of vanilla linger on the finish.

Blend: 85% Garnacha, 15% Tempranillo

Where to Buy: LCBO (24,95$), SAQ (19,90$)

Muga Reserva 2012 (red) – 89pts. PW

Intense red cherry, strawberry and dark fruit aromas underscored by licorice and vanilla nuances. A fresh, lively attack leads into a broad, dry, grainy-textured palate of medium weight. Tart red and black fruits linger through to the medium length finish. American oak nuances (vanilla, dill) are tempered with hints of spicy, cedar scented French oak.

Blend: 70% Tempranillo, 20% Garnacha, 7% Mazuelo, 3% Graciano

Where to Buy: LCBO (23,95$), SAQ (23,35$)

Bodegas Palacio “Glorioso” Reserva 2012 (red) – 90pts. PW

Elegant, yet somewhat restrained nose featuring prunes, baking spice, cassis and dark cherries. Upon aeration hints of citrus and fresh strawberries emmerge. The palate offers brisk acidity, a powerful, tightly knit structure and firm tannins. The finish is lengthy and nuanced, with lingering cedar oak notes. Needs time in cellar to unwind, or several hours decanting before serving.

Blend: 100% Tempranillo

Where to Buy: SAQ (25,50$)

Marqués de Murrieta “Ygay” Reserva 2011 (red) – 91pts. PW

Pretty, fragrant nose featuring crushed strawberries, dark cherry and spice, underscored by earthy, leather nuances. Quite elegant on the palate, with fresh acidity ably balanced by the bright fruit. Slightly lean on the mid-palate, though finishes well, with fine grained tannins and nicely integrated toasty, vanilla oak.

Blend: 92% Tempranillo, 3% Mazuelo, 3% Garnacha, 2% Graciano

Where to Buy: SAQ (27,25$)

Cune Gran Reserva 2009 (red) – 92pts. PW

The elegant nose features ripe plum, blackberry, red cherry, vanilla and cedar notes, with hints of dried fruit, leather and spice developing upon aeration. Very silky and plush on the palate, with rounded acidity, full body and loads of ripe plum and vanilla flavours. The tannins are moderately firm, yet velvetty in texture framing the finish nicely. Only moderate concentration and intensity prevent an even higher rating for this, nevertheless, attractive Gran Reserva.

Blend: 85% Tempranillo, 10% Graciano, 5% Mazuelo

Where to Buy: LCBO (38,95$), SAQ – 2008 vintage (27,85$)

CVNE “Viña Real” Gran Reserva 2008 (red) – 92pts. PW

Heady aromas of stewed strawberries, licorice and morello cherries are nicely counterbalanced by attractive earthy notes. Fresh and full bodied on the palate, yet already quite mellow with wonderful depth of flavour and a long, harmonious finish. The tannins remain firm, but the oak is already well integrated.

Blend: 95% Tempranillo, 5% Graciano

Where to Buy: SAQ (35,50$), LCBO – 2008 vintage (37,00$)

CVNE “Imperial” Gran Reserva 2009 (red) – 94pts. LW

Intense, highly complex aromas of tar, tobacco, dark fruits and floral notes are underscored by spicy, vanilla nuances. The palate is fresh, full bodied and dense, yet reveals a pleasantly fleshy texture with time in glass. A highly concentrated core of ripe, dark fruits lifts the mid-palate. The finish is somewhat impenetrable at present, with muscular tannins and pronounved toasty, vanilla oak. Needs additional cellaring (4 – 5 years minimum) to harmonize further.

Blend: 85% Tempranillo, 10% Graciano, 5% Mazuelo

Where to Buy: SAQ (52,25$)